Drawing on Cocktail Napkins Art Books

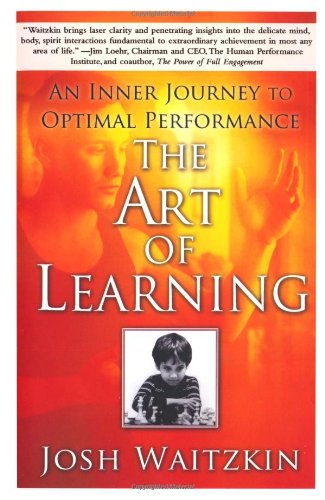

Josh Waitzkin has led a full life as a chess master and international martial arts champion, and as of this writing he isn't yet 35. The Art of Learning: An Inner Journey to Optimal Performance chronicles his journey from chess prodigy (and the subject of the movie Searching for Bobby Fischer) to world championship Tai Chi Chuan with important lessons identified and explained along the way.

Marketing expert Seth Godin has written and said that one should resolve to change three things as a result of reading a business book; the reader will find many lessons in Waitzkin's volume. Waitzkin has a list of principles that appear throughout the book, but it isn't always clear exactly what the principles are and how they tie together. This doesn't really hurt the book's readability, though, and it is at best a minor inconvenience. There are many lessons for the educator or leader, and as one who teaches college, was president of the chess club in middle school, and who started studying martial arts about two years ago, I found the book engaging, edifying, and instructive.

Waitzkin's chess career began among the hustlers of New York's Washington Square, and he learned how to concentrate among the noise and distractions this brings. This experience taught him the ins and outs of aggressive chess-playing as well as the importance of endurance from the cagey players with whom he interacted. He was discovered in Washington Square by chess teacher Bruce Pandolfini, who became his first coach and developed him from a prodigious talent into one of the best young players in the world.

The book presents Waitzkin's life as a study in contrasts; perhaps this is intentional given Waitzkin's admitted fascination with eastern philosophy. Among the most useful lessons concern the aggression of the park chess players and young prodigies who brought their queens into the action early or who set elaborate traps and then pounced on opponents' mistakes. These are excellent ways to rapidly dispatch weaker players, but it does not build endurance or skill. He contrasts these approaches with the attention to detail that leads to genuine mastery over the long run.

According to Waitzkin, an unfortunate reality in chess and martial arts—and perhaps by extension in education—is that people learn many superficial and sometimes impressive tricks and techniques without developing a subtle, nuanced command of the fundamental principles. Tricks and traps can impress (or vanquish) the credulous, but they are of limited usefulness against someone who really knows what he or she is doing. Strategies that rely on quick checkmates are likely to falter against players who can deflect attacks and get one into a long middle-game. Smashing inferior players with four-move checkmates is superficially satisfying, but it does little to better one's game.

He offers one child as an anecdote who won many games against inferior opposition but who refused to embrace real challenges, settling for a long string of victories over clearly inferior players (pp. 36-37). This reminds me of advice I got from a friend recently: always try to make sure you're the dumbest person in the room so that you're always learning. Many of us, though, draw our self-worth from being big fish in small ponds.

Waitzkin's discussions cast chess as an intellectual boxing match, and they are particularly apt given his discussion of martial arts later in the book. Those familiar with boxing will remember Muhammad Ali's strategy against George Foreman in the 1970s: Foreman was a heavy hitter, but he had never been in a long bout before. Ali won with his "rope-a-dope" strategy, patiently absorbing Foreman's blows and waiting for Foreman to exhaust himself. His lesson from chess is apt (p. 34-36) as he discusses promising young players who focused more intensely on winning fast rather than developing their games.

Waitzkin builds on these stories and contributes to our understanding of learning in chapter two by discussing the "entity" and "incremental" approaches to learning. Entity theorists believe things are innate; thus, one can play chess or do karate or be an economist because he or she was born to do so. Therefore, failure is deeply personal. By contrast, "incremental theorists" view losses as opportunities: "step by step, incrementally, the novice can become the master" (p. 30). They rise to the occasion when presented with difficult material because their approach is oriented toward mastering something over time. Entity theorists collapse under pressure. Waitzkin contrasts his approach, in which he spent a lot of time dealing with end-game strategies

where both players had very few pieces. By contrast, he said that many young students begin by learning a wide array of opening variations. This damaged their games over the long run: "(m)any very talented kids expected to win without much resistance. When the game was a struggle, they were emotionally unprepared." For some of us, pressure becomes a source of paralysis and mistakes are the beginning of a downward spiral (pp. 60, 62). As Waitzkin argues, however, a different approach is necessary if we are to reach our full potential.

A fatal flaw of the shock-and-awe, blitzkrieg approach to chess, martial arts, and ultimately anything that has to be learned is that everything can be learned by rote. Waitzkin derides martial arts practitioners who become "form collectors with fancy kicks and twirls that have absolutely no martial value" (p. 117). One might say the same thing about problem sets. This is not to gainsay fundamentals—Waitzkin's focus in Tai Chi was "to refine certain fundamental principles" (p. 117)—but there is a profound difference between technical proficiency and true understanding. Knowing the moves is one thing, but knowing how to determine what to do next is quite another. Waitzkin's intense focus on refined fundamentals and processes meant that he remained strong in later round while his opponents withered. His approach to martial arts is summarized in this passage (p. 123):

"I had condensed my body mechanics into a potent state, while most of my opponents had large, elegant, and relatively impractical repertoires. The fact is that when there is intense competition, those who succeed have slightly more honed skills than the rest. It is rarely a mysterious technique that drives us to the top, but rather a profound mastery of what may well be a basic skill set. Depth beats breadth any day of the week, because it opens a channel for the intangible, unconscious, creative components of our hidden potential."

This is about much more than smelling blood in the water. In chapter 14, he discusses "the illusion of the mystical," whereby something is so clearly internalized that almost imperceptibly small movements are incredibly powerful as embodied in this quote from Wu Yu-hsiang, writing in the nineteenth century: "If the opponent does not move, then I do not move. At the opponent's slightest move, I move first." A learning-centered view of intelligence means associating effort with success through a process of instruction and encouragement (p. 32). In other words, genetics and raw talent can only get you so far before hard work has to pick up the slack (p. 37).

Another useful lesson concerns the use of adversity (cf. pp. 132-33). Waitzkin suggests using a problem in one area to adapt and strengthen other areas. I have a personal example to back this up. I will always regret quitting basketball in high school. I remember my sophomore year—my last year playing—I broke my thumb and, instead of focusing on cardiovascular conditioning and other aspects of my game (such as working with my left hand), I waited to recover before I got back to work.

Waitzkin offers another useful chapter entitled "slowing down time" in which he discusses ways to sharpen and harness intuition. He discusses the process of "chunking," which is compartmentalizing problems into progressively larger problems until one does a complex set of calculations tacitly, without having to think about it. His technical example from chess is particularly instructive in the footnote on page 143. A chess grandmaster has internalized much about pieces and scenarios; the grandmaster can process a much greater amount of information with less effort than an expert. Mastery is the process of turning the articulated into the intuitive.

There is much that will be familiar to people who read books like this, such as the need to pace oneself, to set clearly defined goals, the need to relax, techniques for "getting in the zone," and so forth. The anecdotes illustrate his points beautifully. Over the course of the book, he lays out his methodology for "getting in the zone," another concept that people in performance-based occupations will find useful. He calls it "the soft zone" (chapter three), and it consists of being flexible, malleable, and able to adapt to circumstances. Martial artists and devotees of David Allen's Getting Things Done might recognize this as having a "mind like water." He contrasts this to "the hard zone," which "demands a cooperative world for you to function. Like a dry twig, you are brittle, ready to snap under pressure" (p. 54). "The Soft Zone is resilient, like a flexible blade of grass that can move with and survive hurricane-force winds" (p. 54).

Another illustration refers to "making sandals" if one is confronted with a journeyacross a field of thorns (p. 55). Neither bases "success on a submissive world or overpowering force, but on intelligent preparation and cultivated resilience" (p. 55). Much here will be familiar to creative people: you're trying to think, but that one song by that one band keeps blasting away in your head. Waitzkin's "only option was to become at peace with the noise" (p. 56). In the language of economics, the constraints are given; we don't get to choose them.

This is explored in greater detail in chapter 16. He discusses the top performers, Michael Jordan, Tiger Woods, and others who do not obsess over the last failure and who know how to relax when they need to (p. 179). The experience of NFL quarterback Jim Harbaugh is also useful as "the more he could let things go" while the defense was on the field, "the sharper he was in the next drive" (p. 179). Waitzkin discusses further things he learned while experimenting in human performance, particularly with respect to "cardiovascular interval training," which "can have a profound effect on your ability to quickly release tension and recover from mental exhaustion" (p. 181). It is that last concept—to "recover from mental exhaustion"—that is likely what most academics need help with.

There is much here about pushing boundaries; however, one must earn the right to do so: as Waitzkin writes, "Jackson Pollock could draw like a camera, but instead he chose to splatter paint in a wild manner that pulsed with emotion" (p. 85). This is another good lesson for academics, managers, and educators. Waitzken emphasizes close attention to detail when receiving instruction, particularly from his Tai Chi instructor William C.C. Chen. Tai Chi is not about offering resistance or force, but about the ability "to blend with (an opponent's) energy, yield to it, and overcome with softness" (p. 103).

The book is littered with stories of people who didn't reach their potential because they didn't seize opportunities to improve or because they refused to adapt to conditions. This lesson is emphasized in chapter 17, where he discusses "making sandals" when confronted with a thorny path, such as an underhanded competitor. The book offers several principles by which we can become better educators, scholars, and managers.

Celebrating outcomes should be secondary to celebrating the processes that produced those outcomes (pp. 45-47). There is also a study in contrasts beginning on page 185, and it is something I have struggled to learn. Waitzkin points to himself at tournaments being able to relax between matches while some of his opponents were pressured to analyze their games in between. This leads to extreme mental fatigue: "this tendency of competitors to exhaust themselves between rounds of tournaments is surprisingly widespread and very self-destructive" (p. 186).

The Art of Learning has much to teach us regardless of our field. I found it particularly relevant given my chosen profession and my decision to start studying martial arts when I started teaching. The insights are numerous and applicable, and the fact that Waitzkin has used the principles he now teaches to become a world-class competitor in two very demanding competitive enterprises makes it that much easier to read.

I recommend this book to anyone in a position of leadership or in a position that requires extensive learning and adaptation. That is to say, I recommend this book to everyone.

More About Learning

- 13 Ways to Develop Self-Directed Learning and Learn Faster

- How to Learn Fast and Remember More: 5 Effective Techniques

- How to Create an Effective Learning Process And Learn Smart

Featured photo credit: Jazmin Quaynor via unsplash.com

Drawing on Cocktail Napkins Art Books

Source: https://www.lifehack.org/articles/lifehack/a-review-of-the-art-of-learning.html

0 Response to "Drawing on Cocktail Napkins Art Books"

ارسال یک نظر